In this article, we discuss the peculiarities of long-term economic convergence of the Baltic states to the European economy. The world financial crisis and its impact on the region make this subject of particular interest as the region’s rapid growth was interrupted. We discuss with local financial analysts blaming the Lithuanian monetary regime as the primary source of instability. The book Anatomy of the Crisis in Lithuania by Stasys Jakeliunas, published at the end of 2010, is an example of a traditional view of the crisis in the Baltic states. Partially it reflects the widely accepted interpretation of financial crisis dynamics in the Baltic States by foreign experts as well.

First, we show how and why the Baltic countries’ approach to the Economies of developed countries and the Key sources of such development. At first glance, one can conclude that Lithuania’s real GDP growth at constant prices does not exhibit any considerable increase in the long term starting from 1990. Nevertheless, we invite you to get more careful consideration based on the widely available data from the International Monetary Fund and World Bank published on the website www.tradingeconomics.com.

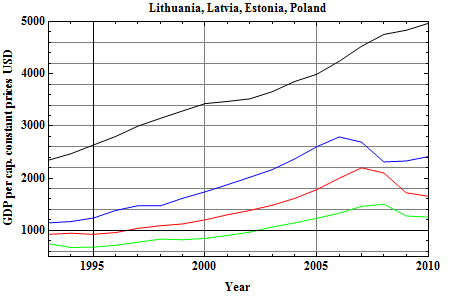

In Fig. 1. we provide the real GDP growth at constant prices of the three Baltic States and Poland from 1993 to 2010. Here GDP growth is given in U.S. dollars per capita, i.e., the GDP per capita in 1993, denominated in U.S. dollars, is multiplied yearly by the actual annual GDP growth. Only such slow growth is obtained if we remove the price growth, i.e., consider the inflation-adjusted GDP. In this Figure, Lithuania looks like a very slowly developing country. Lithuania is at the lowest level from the beginning of the period considered; its GDP per capita was 1.24, 1.54, and 3.15 times less than the GDP of Latvia, Estonia, and Poland, respectively. The real GDP growth until 2010 did not improve; contrarily, the differences with the same countries became 1.33, 1.97, and 4.1-times, respectively.

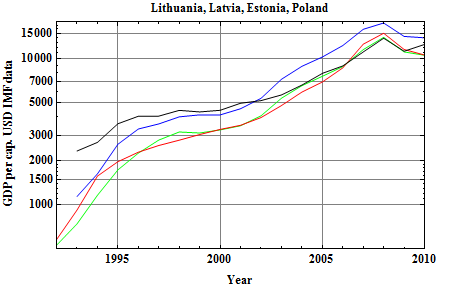

How this picture looks when GDP is calculated in current year prices? The GDP per capita at current prices is given in Fig. 2.

GDP growth in the illustration is shown on a Logarithmic scale since it changes a dozen times; for example., Lithuania’s GDP grew More than 14 times Latvia, Estonia, and Poland’s, respectively 11.5, 12.2, and 5.4-times. Growth rates in this view turned quite the opposite. Skeptics may deny the reality of this growth because it is offset by inflation. However, there is no doubt that during the period considered, the contribution of these countries to the Global economy grew to a similar extent. Therefore, the rate of convergence of the economies has to be determined by current prices calculated with the same worldwide used currency, not by the so-called real GDP growth. The actual scale of economic convergence is hidden in the GDP deflator, not real GDP growth.

So what might seem like a hopeless Lithuania’s economic backwardness turns into a success story. Its relative growth rate is the highest in the Baltics. Despite pretty different fiscal and other policies implemented, nominal GDP growth in the Baltic countries, by a whole range of nature, are virtually identical. The most significant difference is related to different initial conditions. The universal similarity of macroeconomic change in Baltic countries probably is related to very similar monetary policy – national currencies are pegged to the Euro. In our opinion, the public debate on economic issues in the Baltic countries pays too much attention to microeconomics when the critical macroeconomic and monetary issues in the general discussion are often misunderstood.

For a better understanding of Baltic development, a comparison with the economy of neighboring Poland is very valuable. Poland’s GDP per capita in 1993 was more than three times the GDP of Lithuania. It only took 13 years to overcome the backwardness of Lithuania, and Estonia had to cope with a smaller gap, surpassing Poland in nine years. The significant differences in the Polish economy are related to the size and monetary regime. Baltic countries experienced a second rapid growth since 2000 as bank credits grew considerably in this period. See our previous publication, What banking analysts conceal about financial crisis in the Baltic States, for more details about domestic credit growth in Baltic countries.

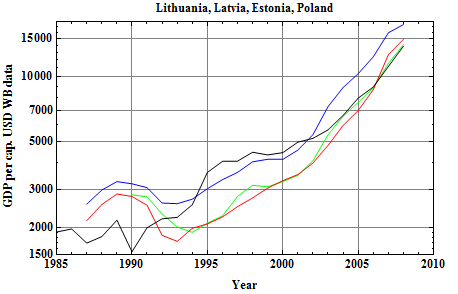

In Fig. 3, one can see even more details on how monetary changes impact the economies in transition. We present World Bank (WB) data on GDP per capita in USD for the same countries. Note that WB data is extended to the period from 1985 and has considerable differences with IMF data before 1996. Having in mind that this data may contain significant uncertainties, nevertheless, one can have an opportunity to analyze GDP sensitivity to the monetary decisions of that period. The currency board introduced in Baltic countries around 1994 is a great advantage.

The evident relation of economic convergence with price and GDP levels is not widely accepted among financial analysts. This misunderstanding leads to the overestimated use of real GDP growth in the analysis of economic growth. From our point of view, the economic growth in such transition countries as the Baltic States is indispensable from inflation and domestic credit. Usual scenarios of the financial crisis have to be considered differently for countries in transition as they have space for price movement. Though all financial crises have a common background, the risk of developing countries is very often overestimated and leads to considerable losses in these countries. The experience of the Baltic States in the present global crisis will serve as an example of how the policy of foreign banks may cause a profound disturbance to the economy. Baltic countries’ ability to recover without real help after the shock therapy will serve as an example of groundless financial risk estimates.